Folding Emacs Into Keyboard Firmware

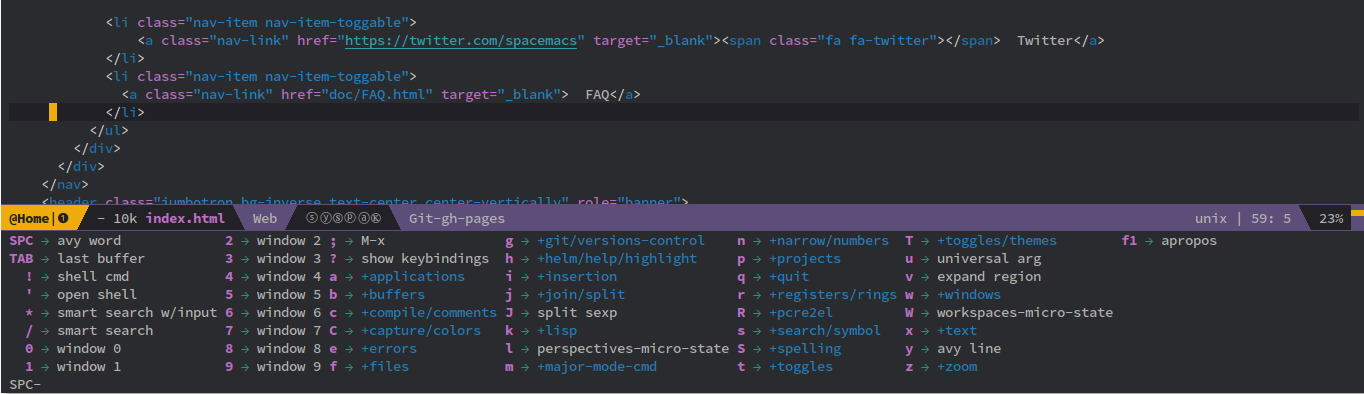

Emacs has been my daily-driver editor for a few years. To be precise, I was maining Spacemacs in its Emacs-flavored Holy mode, in contrast to its Vim-flavored Evil mode.

The defining mechanic of Spacemacs is arguably the use of leader commands. After pressing a designated leader key, you’d chain a sequence of other keys to compactly spell out a command. For instance, to find a file, you’d chord together f f after the leader key. To make an in-editor window maximized, you’d do w m, while w d would delete it. To get some help in the form of the description of a function, h d f. To get to a git file history, you’d say g f h. Through its bundle of add-ons and strong defaults, Spacemacs would show you what different keys are useful for as you’re typing out a leader command.

This has been a solid user experience; I’ve edited an entire interactive book in this setup. That was fine, until — cue horror music — the dreaded Emacs pinky. Basically, the combination of modifier-heavy Emacs mechanics, a keyboard that was compact yet had poor ergonomics, and a non-trivial typing volume, resulted in a painful typing experience. This was a call for adventure, kicking off a journey into keyboard ergonomics and interaction design. Come along.

I’ve met a number of oddities along the way. Keyboards that are split in two halves. Keyboards whose keys are arranged ortholinearly. Keyboards whose split halves are tented, and whose keycaps are tilted. But what I found most unexpected had nothing to do with ergonomics in the traditional sense.

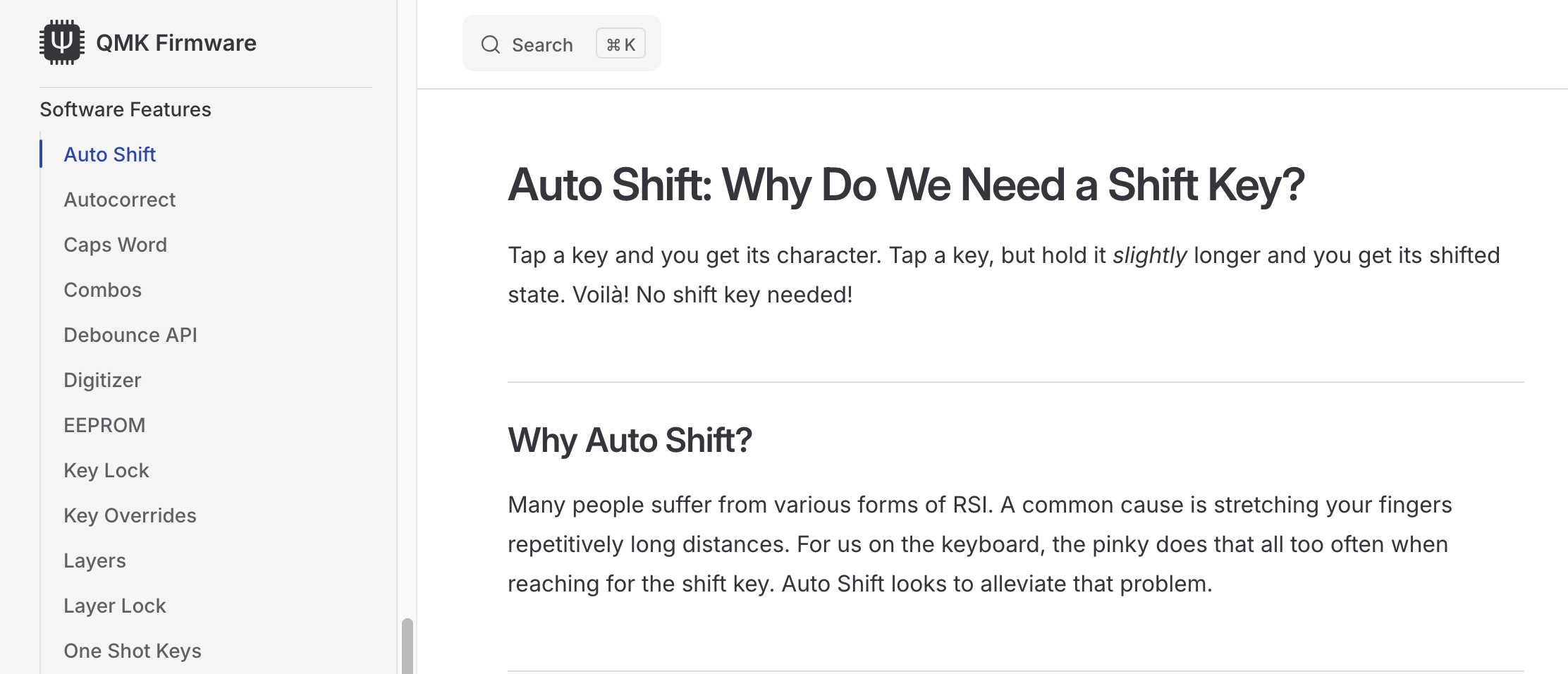

It turns out that many of these obscure, hobbyist keyboards also allow users to customize how keys work and what keys mean. By flashing a custom QMK firmware on the actual chip contained in the keyboard, you tap into a whole new dimension of human-computer interaction.

Having journeyed this far, we encountered even more exotic specimens. Auto shift makes keys emit shifted versions of their core keycode when held. Tap dances can make keys work differently when tapped in different patterns. Repeat keys can replay the last keycode, including its modifiers. And because these affordances are burned into the keyboard itself, they work natively when connecting it to a different machine, with a different operating system.

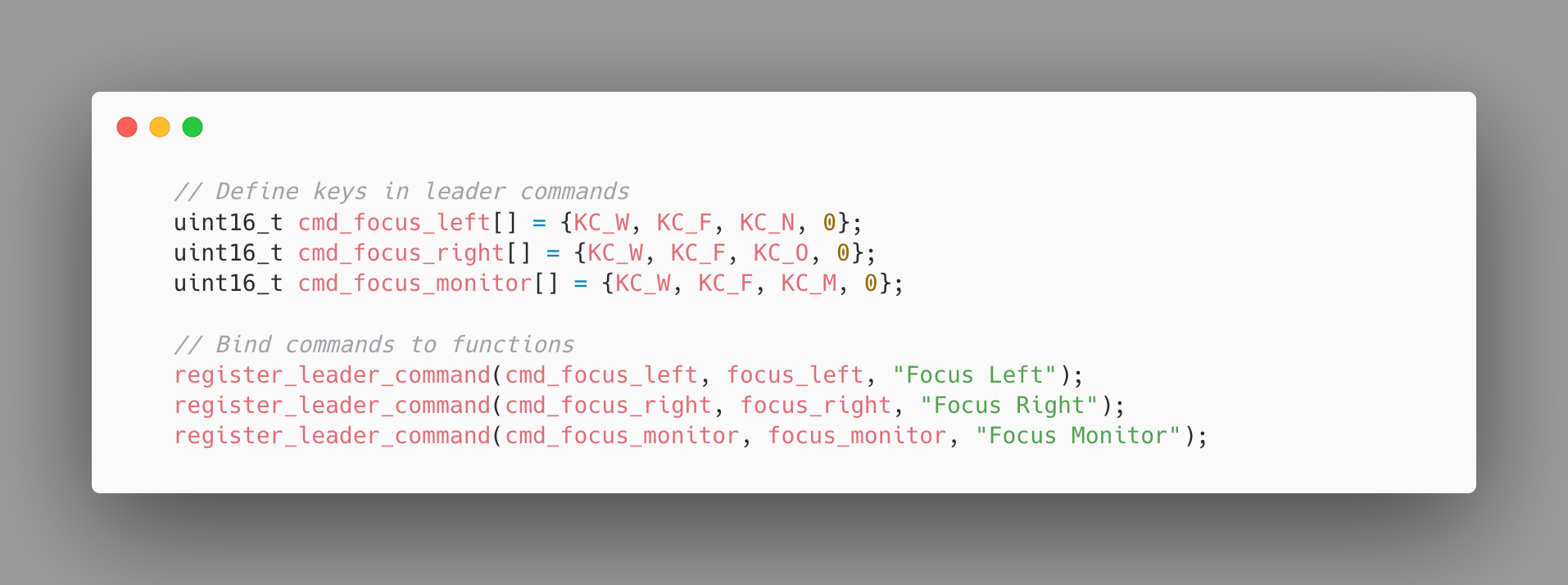

Among other explorations of user experience, we encounter a familiar face, the leader key. You can configure the firmware itself to process leader commands and do things according to their contents, with the actual leader key being placed in a thumb cluster perhaps. Hm, interesting.

At this point I started wondering what it would take to fold Emacs mechanics into the keyboard itself, and issue mnemonic leader commands at the operating system level. Chords for moving across panes in any app, for running git operations seamlessly, for manipulating text in and out of assistant chats (this was before referencing files in Cursor), among others. But it turned out the predefined leader key functionality wasn’t powerful enough to approach feature-parity with the Emacs experience in subtle ways, and so I implemented a custom version in base QMK. I’m calling the result Spacecaps.

The basics were similar enough to the original version. Instead of polluting the predefined callback for processing the end of a leader command, you could register pairs of key sequences and triggered functions from different places in the firmware codebase. In addition, the keycaps associated with valid continuations of the current leader command would physically light up. On each step of a leader command, the keyboard would also emit serial logs with human-readable descriptions of possible continuations, to be picked up by a learning utility.

Beyond this core, there were four Emacs affordances which had to be addressed individually. First, Emacs has “major modes,” which represent different editing contexts, such as Python mode or Markdown mode. When you’re in a major mode, leader commands might operate slightly differently, depending on context. In the keyboard setting, it’s difficult to get information on the current state of the machine, as it’s mostly an input peripheral. The solution was to configure the leader commands which cause context switching, such as ones focusing an app or an app area, to also store that information on the keyboard. For instance, if (a)pplication (s)hell focuses VS Code and then also focuses its terminal, it must also update a local variable with the last launched context. In turn, subsequent leader commands can take this state into account, enabling, for example, a unified set of leader commands for natively navigating across panes of different apps, even if the apps have different keyboard bindings.

Second, Emacs has a really pleasant mechanic called transient modes. You launch these temporary modes by going down specific leader command branches, and they essentially provide a thematic grouping of single-key commands to execute from there on. For instance, after you reach the window transient mode, you can issue single keypresses to move panes around, tweak their size, etc. These are the kinds of commands which get executed repeatedly, one after another, in close succession. It would be quite tedious to have to reissue full-size leader commands for each such tweak. The solution in the keyboard setting was what I’d like to call “prefix locking.” Think of all registered leader commands as forming a prefix tree of keys. A full command gets from the leader key root to a tree leaf. Well, when you toggle prefix locking, you “lock” the keys in the leader command which you have already pressed. When you then complete a command, you get placed back at the end of the prefix, meaning that if some “suffixes” are one-key long, you achieve a de facto transient mode. Better still, prefix locking makes it possible to turn any place in the prefix tree of leader commands into a transient mode, and have suffixes that are multiple keys long. The available keys turn green, until you toggle prefix locking off.

I noticed that what my favorite computer science projects have in common is functional purity: JAX can turn NumPy-like functions into their vectorized versions, their gradients, or their JIT-compiled versions; Nix enables wonders by treating packages as pure functions of their dependencies; Haskell broke my brain in the most delightful way possible. Emacs has a seedling of this in the form of commands which modify the effects of other commands. They might repeat them, reverse their direction, fetch their documentation, etc. The way to transfer this mechanic is to recognize that the leaves of our prefix tree have triggered functions attached to them as pointers. And so we might have a function which simply replays the last function, a bit like QMK’s repeat key implementation but with entire commands as the unit of repetition. Similar possibilities are afforded by the other typical functionals: map, filter, reduce, etc. For instance, you can map commands to a predefined inverse, such as going forwards or backwards in time in a web browser or music player.

The fourth and final substantial feature here is for moving up and down the ladder of abstraction. It’s easier to dream up machine learning ideas when working in Python over Assembly. Being able to abstract away from the details is powerful, and I wanted to easily move from the tactical level of moving things around to the strategic level of what I’m trying to accomplish. For instance, I might move from the code editor to the shell, kill the current process, get the previous command, run it, move back to the editor. Or, I might want to merge these in a unified “rerun last command” abstraction on the go, depending on what command chains I find myself issuing often. QMK’s dynamic macros implementation proved quite powerful out of the box, as it handles the recording and replay of a sequence of keypresses, even if it necessarily isn’t tracking local state changes from context switches and such.

This was the story of Spacecaps, an attempt to fold Spacemacs into keyboard firmware, with all the low-level learnings that entailed. This is more of a post-hoc write-up I wanted to have in place before getting to a new hobby project on the same interaction design front. A story for another time.